This article is about Special Operations conducted by Allied forces (Great Britain and United States) against Japanese forces during second world war in India-Burma theater. In general, South-East Asia theater is less popular than other war zones of second world war. Allied main focus was naturally Europe, Middle East, Africa and Pacific zones. We hear many stories of special operations and various exploits from those zones. This article tries to highlight one of the similar exploits from South-East Asia theater through postal covers.

Even though, we have various Virk ([1], [2]) and Proud ([3], [4]) catalogues/books available to refer (from FPO usage point of view), some of the fighting units are poorly documented. Sometimes, we see conflicting information among (about usage of Indian/British FPOs by various units) them. I have tried my best to present information as much as possible accurately, but there is possibility of the errors. I would request experts to point out any such mistakes, missing information and provide their valuable feedback.

Every special operation conducted during WW2 had its own purpose and clearly defined objective e.g., sabotage enemy plans or assist main fighting forces to defeat them, sometimes they were also used as a propaganda tool even in case of failure of such operation. In some historian’s view ‘Chindits’ operations were one of them. They were viewed as propaganda tool in the beginning specially their first offensive called ‘Operation Longcloth’ which then set path for second and wider offensive known as ‘Operation Thursday’. We would mostly focus on the latter offensive in this article via British/Indian FPO covers from the said period and modern day (post-Independence) Indian Army Postal Service covers commemorating some of those Indian units which participated in it.

About the Chindits (quick

introduction)

The Chindits, officially known as Long Range Penetration Groups (LRP), were special operations units of the British and Indian armies (also consisted of Africans, Americans, Burmese, Chinese and other allied nationalities) which saw action in 1943–1944 during the Burma Campaign of World War II.

The British Army Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate formed the Chindits (Long Range Penetration Groups) for raiding operations against the Imperial Japanese Army, attacking Japanese troops, facilities, and lines of communication deep behind Japanese lines. Their operations featured long marches through extremely difficult terrain, undertaken by underfed troops often weakened by diseases such as malaria and dysentery.

Controversy persists over the extremely high casualty-rate and the debatable military value of the achievements of the Chindits. Historians have different views on Chindits operations such as they believed Wingate’s ideas were flawed in many respects. For one thing, the Imperial Japanese Army did not have Western-style supply lines to disrupt and tended to ignore logistics generally. When Special Force launched itself into Burma in March 1944, Wingate’s ideas rapidly proved unworkable. However, Mutaguchi Renya (the commander of the Japanese 15th Army), later stated that ‘Operation Thursday’ had a significant effect on the campaign, saying "The Chindit invasion had a decisive effect on these operations. They drew off the whole of 53rd Division and parts of 15th Division, one regiment of which would have turned the scales at Kohima".

Operation Longcloth as propaganda tool

Even though first Chindit offensive ‘Operation Longcloth’ which took place between February and June 1943 was a military disaster and many officers in the British and Indian army questioned the overall value of the Chindits based on the losses incurred during the first long-range jungle penetration operation (LRP), Wingate viewed it as a psychological triumph.

He sent 61-pages operation report back to London (which was also passed on to Churchill) which viewed the Chindits and their exploits as a success after the long string of Allied disasters in the Far East theatre. Churchill, an ardent proponent of commando operations, was complimentary toward the Chindits and their accomplishments. It was seen as a propaganda tool which proved that Japanese could be beaten, and British/Indian troops could successfully operate in the jungle against experienced Japanese forces.

>Churchill was so much impressed that he asked Wingate to travel with him to The First Quebec Conference, codenamed ‘Quadrant’. It was a highly secret military conference held during WW2 by the governments of the Great Britain, Canada, and the United States. It took place in Quebec City on August 17–24, 1943, at both the Citadelle and the Château Frontenac

Fig 1: Major General Orde Charles Wingate

Concept of Long-Range Penetration (LRP) Operation and birth

of ‘Operation Thursday’

At the Quebec Conference in 1943, Wingate explained his ideas to Franklin D Roosevelt, and other leaders. Wingate proposed creating strongholds in enemy territory that would be supplied by air and be as effective against the enemy as conventional troops. He presented ideas of deep penetration operations that could be made possible through improvements in the range of communication devices and airborne supply by long range aircraft.

It was decided that operations against Japan would be intensified in order to exhaust Japanese resources, cut their communications lines, and secure forward bases from which the Japanese mainland could be attacked. Wingate was promoted to Major General and given green signal to plan for second offensive.

The second long-range penetration mission was originally intended as a coordinated effort with a planned regular army offensive against Japanese forces in northern Burma, but events on the ground resulted in cancellation of the army offensive, leaving the long-range penetration groups without a means of transporting into Burma. Upon Wingate's return to India, he found that his mission had also been cancelled for lack of air transport. He took the news bitterly, voicing disappointment to all who would listen, including Allied commanders such as Colonel Philip Cochran of the 1st Air Commando Group (USAAF). Cochran told Wingate that cancelling the long-range mission was unnecessary; only a limited amount of aerial transport would be needed since, in addition to the light planes and C-47 Dakotas Wingate had counted on, Cochran explained that 1st Air Commando had 150 gliders to haul supplies. Thus, a new plan was formed relying on gliders to drop brigades in Burma.

Units of 2nd Long Range Penetration

Offensive (Operation Thursday)

While first Chindit offensive had jungle long range penetration unit created from 77th Indian Infantry Brigade which were trained at a special camp setup (Fig 2) at Saugor district in central India, for second offensive Wingate was given six brigades (77th Indian Infantry, 111th Indian Infantry, 14th Brigade of British 70th Division, 16th Brigade of British 70th Division, 23rd Brigade of British 70th Division and 3rd West African Brigade of 81st West African Division).

77th Indian Infantry Brigade (also known as

“EMPHASIS”)

At the heart of this operation was existing 77th Indian Infantry Brigade (first LRP). They continued to train in jungles of central India until Dec’43 (by [3]) or Feb’44 (by [1]) when finally, they were given order to move towards forward bases of North-East India for the campaign.

Indian FPO 81 was used by 77th Indian Infantry Brigade until March 1944 before they entered Burma. FPO didn’t go with them. Wingate planned that part of 77th Brigade would land by glider (as per new plan) in Burma and prepare airstrips into which 111th Brigade and the remainder of 77th Brigade would be flown by C-47 Dakota aircraft. Two landing sites codenamed "Piccadilly" and "Broadway" were selected. On the evening of 5th March 1944 as Wingate, Lieutenant General Slim (the commander of Fourteenth Army), Brigadier Michael Calvert (the commander of 77th Brigade) and Cochran waited at Lalaghat airfield in India for 77th Brigade to fly into "Piccadilly", an incident occurred.

Fig 4: On Golden

Jubilee of 77 Mountain Brigade (Chindits), Indian Army Postal Service issued

APS cover commemorating their exploits in 1992.

Fig 5:

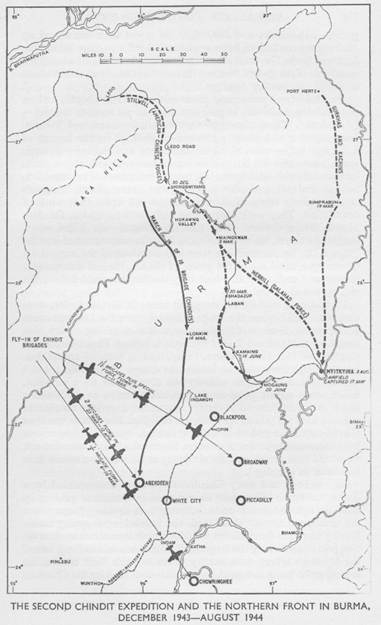

Operation Thursday Air Launch Map

Wingate had forbidden continuous reconnaissance of the landing sites to avoid compromising the security of the operation, but Cochran ordered a last-minute reconnaissance flight which showed "Piccadilly" to be completely obstructed with logs. There was confusion that the operation had been betrayed, and that the Japanese would have set up ambushes on the other two landing sites. Slim still ordered that the operation was to go ahead. Wingate then ordered that 77th Brigade would fly into "Chowringhee" (new landing site). Both Cochran and Calvert objected, as "Chowringhee" was on the wrong side of the Irrawaddy and Cochran's pilots were not familiar with the layout. Eventually, "Broadway" was selected instead.

Despite the last-minute drama, the operation was finally flagged off half an hour after the planned time at 18:12. Each C-47 Dakota towed two gliders – all were overloaded to at least 4500 pounds, bouncing and swaying all the way down the airstrip, headed for the Chin Hills in the darkened sky. The original plan called for 40 gliders to go to both Piccadilly and Broadway but finally all 80 would go to Broadway starting the airborne stage of ‘Operation Thursday’. The mission was no longer in the hands of Wingate and his staff; it rested with the pilots of the 1st Air Commando Group. In all, 35 gliders crash landed on Broadway that night. Fortunately, the Japanese were unaware of the landings.

1st Air Commando Group of USAAF

Fig 6: Cover sent from US APO 690 Ondal, India to USA on 11th Feb 1945 with Passed by US Army Examiner 13676 handstamp. It was sent by 6th Fighter Squadron of 1st Air Commando Group.

To comply with Roosevelt's proposed air support for British long range penetration operations in Burma (agreed during Quebec conference), the United States Army Air Forces (USAAAF) created the 5318th Air Unit to support the Chindits. In March 1944, they were designated the 1st Air Commando Group by USAAF Commander General Hap Arnold. Arnold chose Colonel John R. Alison and Colonel Philip Cochran as co-commanders of the unit. It provided fighter cover, bomb striking power, and air transport services for the Chindits, fighting behind enemy lines in Burma. Operations included airdrop and landing of troops, food, and equipment; evacuation of casualties; and attacks against enemy airfields and lines of communication.

Their first joint operation with the Chindits—Operation Thursday—was the first invasion of enemy territory solely by air and set the precedent for the glider landings of Operation Overload associated with the Normandy Landings on D-Day. They also used helicopters in combat for the first time, executing the first combat medical evacuations. They pioneered the use of air-to-ground rockets.

111th Indian Infantry Brigade (also known as “LEOPARD”)

Unaware of Wingate given authority to have far more ambitious offensive for his second LRP expedition (during Quebec conference), General Wavell (also the Viceroy of India) ordered the formation of 111th Indian Infantry Brigade, along the lines of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade at the same time when Wingate was on the way to India. Wavell intended that the two brigades would operate in tandem with one engaged on operations while the other trained and prepared for the next operation. However, once back in India, Wingate was allowed to have six brigades to achieve the goal. He was known to have a strong dislike for the Indian Army, its diverse troop formations, and its British officers. He maintained that their training in long-range penetration techniques would take longer and their maintenance by air would be difficult due to the varied dietary requirements of different Gurkha and Indian castes and religions, although he had little choice but to accept 111th Brigade.

111th Indian Infantry Brigade was due to flown into Piccadilly on 5/6th March 1944, but as that landing site was unusable, so it flew into “Chowringhee” and “Broadway” instead. This left the brigade dispersed and ineffective until it was reunited at “White City”. The goal for 111th Brigade was to move north and build a new stronghold, codenamed ‘Blackpool’ which would block the railway and main road south of Mogaung. Blackpool was close to the Japanese northern front and was immediately attacked by Japanese 53rd Division with heavy artillery support. Even though a heavy attack against Blackpool was repulsed on 17th May, a second attack on 24th May allowed Japanese to capture vital positions. Because the monsoon had broken and heavy rain made movement in the jungle very difficult, neither 77th Brigade nor 14th Brigade could help 111th Brigade. Finally, it had to abandon Blackpool on 25th May, because the men were exhausted after 17 days of continual combat. They were finally evacuated from Mogaung in the May.

Indian FPO 143 was used by 111th Infantry Brigade until March 1944 before they flew into Burma. The FPO didn’t carry them. From May’1944 onwards same FPO was reallocated to 109 Infantry Brigade (14th Infantry Division).

Fig 7: On Golden Jubilee of 3rd Btn, 4th Gurkha Rifles which was part of 111th Indian Infantry Brigade, Indian Army Postal Service issued APS cover commemorating their exploits in 1990. Part of it was also in Morris Force which harassed Japanese forces in the mountain ranges.

Fig 8: On Platinum

Jubilee of 3rd Btn, 4th Gurkha Rifles which was part of

111th Indian Infantry Brigade, Indian Army Postal Service issued APS

cover commemorating their exploits in 2015. The postmark shows Chindits logo as

well.

16th Infantry Brigade of British 70th Division (also known as

“ENTERPRISE”)

When Wingate returned to India from Quebec conference with authority to implement far more ambitious plans for the second expedition, which required that the force be greatly expanded to a strength of six brigades, he was offered British 70th Division. infantries were required, three brigades (the 14th, 16th and 23rd) were added to the Chindits by breaking up the experienced British 70th Division, much against the wishes of General Slim and other commanders, who wished to use the division in a conventional role.

British 70th Division was a very experienced unit seen action in the Middle East and Africa. Following the Japanese occupation of Malaya, and the consequent threat to India, British 70th Division was withdrawn from the Middle East at the end of Feb 1942 and sent to India. 16th Brigade of British 70th Division, was temporarily detached for service in Ceylon, arriving there on 15th Mar 1942. On 1st Feb 1943, the brigade moved to India to join 70th Division. British FPO 40 accompanied 16th Brigade to Ceylon and Ceylonese stamps were used while they operated there.

Fig 9: Cover sent from Ceylon to England using British FPO 40 in March 1942 (after they just arrived from Middle East) with Passed By Censor 90 handstamp.

The plan for 16th Brigade was different as they were supposed to march to its operational area from Ledo while 77th and 111th Brigades were getting airlifted later. The 16th Brigade began its 350-mile (565-km) overland advance on 5th February 1944 starting ‘Operation Thursday’ officially, avoiding the Japanese by crossing extremely difficult terrain.

It took them close to 4 weeks (5th March 1944) to reach Chindwin River crossing point. It was at the same time (6th March 1944) when Japanese launched Operation ‘U-Go’, an invasion of eastern India. It would take them another tough two weeks march south to reach their first objective, a stronghold named “Aberdeen” (20th March 1944). It existed only on paper and in the mind.

Wingate intended that “Aberdeen” should rise from the ground on the labor and toil of 16th Brigade after their long march. From there they moved towards Indaw. He hoped that the three brigades could then co-operate in the capture of the communications nexus at Indaw, together with its airfield, so that a division could be flown in to hold the area as a base for the Chindit columns roving the Japanese rear areas and wreaking havoc. Though, 16th Brigade failed to occupy Indaw and were withdrawn to India by May 1944.

14th Infantry Brigade of British 70th Division (also known as

“JAVELIN”)

Initially, 14th Brigade was supposed to be held in reserve along with 23rd Brigade and 3rd West African Brigade. But, when Japanese threat at Imphal and Kohima started developing, General Slim thought of diverting 14th Brigade just like he did with 23rd Brigade to help Indian XXXIII Corps. There were tense moments for Wingate as he was furious losing out another of his brigade. Finally, Slim let Wingate keep 14th Brigade for Burma offensive.

The 14th Infantry Brigade was airlifted to ‘Aberdeen’ on 23/24 March 1944 (same time when Wingate died in plane crash). While 16th Brigade thought 14th Brigade would help it capture ‘Indaw’ which was south to Aberdeen, 14th Brigade instead moved north towards ‘Blackpool’ and was involved in heavy fighting in the area with the Japanese. It helped 111th Brigade capture Blackpool in May before eventually it was withdrawn to India in August 1944.

Fig 10: Cover sent within India using British FPO 199 on 23rd August 1944 (after 14th Infantry Brigade was withdrawn to India) with Field Censor 35 and Unit Censor S 471 handstamp.

As

per [4], BFPO 199 was used

by 14th Brigade. It states that as a Special Forces P.O. it was used

from Dec’43-May’44 period. Though, there is some conflicting information on it.

Because, as per same catalogue it also states BFPO 37 was allotted to 14th

Brigade. While, as per [2] [Ch. 22 The Assam

Front, Page 247], it says BFPO 199 was allotted to 23rd Brigade. So,

it can’t be ascertained if BFPO 199 was used by 14th Brigade even

though it was used by one of the units of Special Forces. For now, I am

sticking to Proud where it shows 14th Brigade against BFPO 199.

23rd Infantry Brigade of British 70th

Division

It never joined the Chindits in the field, was instead sent to support XXXIII Indian Corps to quell Japanese attackers (Operation “U-Go” on 6th March 1944) in the Dimapur and Kohima area. But their training as LRP came handy and in fact it was one of the reasons why Japanese 31st division had to retreat when they ran out of supply during the siege of Kohima.

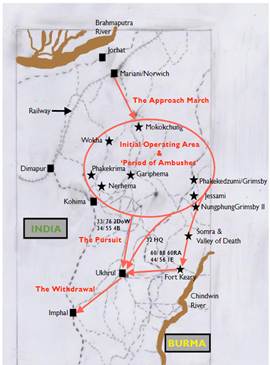

Fig 11: Above diagram shows 23rd Infantry Brigade

action against Japanese 31st division from April-July 1944

Japanese 31st Division had begun the operation with only three weeks supply of food. Once these supplies were exhausted, the Japanese had to exist on meagre captured stocks and what they could forage in increasingly hostile Naga villages. The British 23rd Infantry Brigade, which had been operating behind the Japanese division, cut the Japanese supply lines and prevented them foraging in the Naga Hills to the east of Kohima. Lack of food supply from Japanese Fifteenth Army HQ finally caused Japanese 31st division to withdraw.

As per [4], British FPO 30

was used by 23rd Infantry Brigade in India. While [2] [Ch. 22 The Assam

Front, Page 247], says BFPO 199 was allotted to 23rd Brigade though

it doesn’t provide any further information on it. Similarly, since [1] also doesn’t show

BFPO 199 usage by 23rd Brigade so I am assuming Proud is correct to

state BFPO 30 usage for 23rd Infantry Brigade.

3rd West African Brigade of 81st West

African Division (also known as “THUNDER”)

The 3rd (West African) Brigade was to be used as garrison troops for the strongholds. One battalion was flown into Broadway and made its way on foot to Aberdeen. The other two battalions were flown directly into Aberdeen on 23rd March 1944. The brigade returned to India by August 1944. The brigade was disbanded on 30th November 1944. It then reformed with same units in India on 1st March 1945 coming under command of 81st West Africa Division on 20th March 1945.

All West African Units in Burma (during Chindits operation and afterwards as part of larger Burma campaign) used British FPOs. As per [1]British FPO 670, 696-699 were used by 81st West African Division including their time (Dec 1943 - March 1945) in Burma so perhaps one of those FPOs were used by 3rd West African Brigade as well. I will allow experts to weigh in and share their thoughts.

Fig 13: “On Active Service” cover sent with in India using

British FPO 698 by 81st West African Division along with Unit Censor

G 139 handstamp in March 1945. This is just an example of 81st West

African Division usage in absence of any definitive cover usage by 3rd

West African Brigade.

Other units

Finally, there were Morris Force which harassed Japanese forces in the mountain ridges skirting the Bhamo-Myitkyina Road and then there was DAH Force a small 74 men team which had Kachins of 2nd Burma Rifles as well Chinese from Hong Kong volunteers. DAH was a diversified team with British, Americans, Indians, Kachins and Chinese in it. Besides them there were other units supporting Chindits operations, but I am skipping them to concentrate only on the main ones.

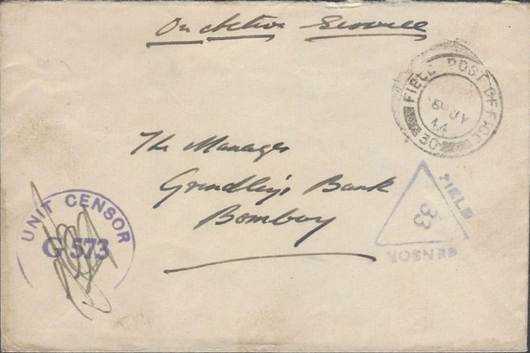

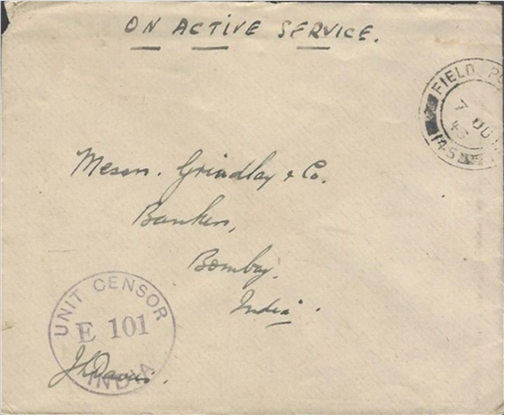

Fig 14: Cover sent

to Bombay, India using British FPO 145 on 7th Jun 1943 (before the

second Chindits offensive) with Unit Censor E 101 handstamp.

As

per Proud and Virk, in general BFPO

30/37/40/145/199 were used by British 70th Division Special Forces

(meant for LRP) at different point in time. So, I am showing usage of BFPO 145

though there is no clear information in either [1] or [3] which British Infantry Brigade was using it.

Fig 15: On Silver Jubilee of 4th Btn, 9th Gurkha Rifles which was part of Morris Force, Indian Army Postal Service issued APS cover commemorating their exploits in 1987. Since the battalion was re-raised in 1961 that’s why it says Silver jubilee although 9th Gorkha Rifles regiment was originally formed by the British in the 1817. On this occasion a special postmark showing Chindits symbol was also issued.

Fig 16: On Diamond Jubilee of 4th Btn, 9th Gurkha Rifles, Indian Army Postal Service issued APS cover commemorating their exploits in 2021. Note that it shows 1961 as starting year as stated earlier.

Conclusion

While Wingate and allies were unaware of timing of Japanese plans of invasion of India, at the same time, Operation Thursday timing just coincided with it and did cause damage to Japanese offensive. As shared earlier in the introduction section while historians have different views on overall effect of the special operations and seen in various Brigade brief history above, the operations may not have achieved its original goal as it had to face strong Japanese Army, it did have huge psychological effect on the Japanese Army as they created havoc by disrupting food supply and communication lines. Chindits used to appear all sudden from dense forest of Burma, attack Japanese columns and used to hide again in the forest well supported by Nisei and Kachins. They created fear in Japanese minds.

Acknowledgement

Some

of the background information including maps have been sourced from Wikipedia. Various FPO usage has been referred from British and

Indian Army Postal Services Catalogues/Books by Proud and Virk as mentioned

below.

References:

[1]

History

of Indian Army Postal Services – D. S. Virk

[2]

Indian Army Post

Offices in the Second World War – D. S. Virk

[3]

History of the Indian Army Postal Service

Volume III - Proud

[4]

British Army Postal Service Vol III –

Proud

I also expect there may be errors on selecting or describing postal history of the FPO covers. Please feel free to correct me and share any relevant FPO covers that one may have (either for exhibit or sale) directly at my email-id jbareria@gmail.com. And do read the second part of the article showcasing American Special Operations which were launched at the same time in my earlier post.