It's almost 11 years since I wrote a blog. I was asked by many well wishers and friends to continue writing, sharing items from my collection. But, I have been lazy (also occupied in personal and professional life). Finally, I decided may be it's time I should break the ice. The article below has been published in Military Postal History Society (MPHS) July'25 edition (Vol 63 No 3). My friend Apratim has also generously published it on his website. I would like to encourage readers to reach out to me with your valuable feedback on it (story, philatelic and ephemera items shown etc.). Also, please browse through Apratim's great website to dive on various aspect of India's freedom struggle and pre-independence history through philately.

I must say it was by chance that I stumbled upon Merrill's Maraduers story. The more I researched the more I got addicted to this special operation. I browsed many websites, US military history archives and read various books on them to understand deeply enspiring, motivating and daring campaign which has almost been forgotten in the pages of the history. I hope you all will like it. Let's not waste any more time. So, here it is ...

Behind Japanese Lines: The American Jungle Force (Merrill's Marauders)

This article is about Special

Operations conducted by Allied forces (primarily United States, Chinese and

British) against Japanese forces during second world war in India-Burma theater.

This operation was launched almost at the same time when Chindits started their

‘Operation Thursday’, and it was complimentary allied effort to recapture Burma.

American strategy in the China Burma India (CBI) theater was

built around keeping China in the war. American war supplies kept the Chinese

fighting. Since the Japanese controlled the Burma Road and the Chinese coast,

the USAAF established an aerial resupply route from Assam, India to Kunming,

China through Himalayan Mountain passes nicknamed “The Hump.” But it was

hazardous and costly. Adverse weather and collisions with cloud-cloaked

mountains caused almost daily aircraft losses. The U.S. needed an alternate

solution. The obvious answer was to build another road that circumvented the

Japanese-controlled Burma Road.

In December 1942, U.S. Army engineers began construction on

the Ledo Road from upper Assam in India. It would cut across north Burma to Lashio,

south of Myitkyina, to meet the original Burma Road. It was a daring effort. The plans for the Ledo Road included

the laying of pipelines, designed to relieve the road and air traffic of

carrying fuel from Assam to China. But a ground campaign was necessary to

secure the route of the Ledo Road through north Burma. That’s where Merrill’s

Marauders special operations came into the picture.

The end goal of this operation was Myitkyina’s capture. General

Stillwell’s idea was by securing its airfield Japanese fighter threat to the

“Hump” resupply line would be eliminated and the USAAF pilots could fly a

shorter and safer route over lower terrain into China. The new lower altitude

air route would reduce gasoline consumption and permit heavier cargos. The city

of Myitkyina could serve as a major supply depot along the Ledo Road route.

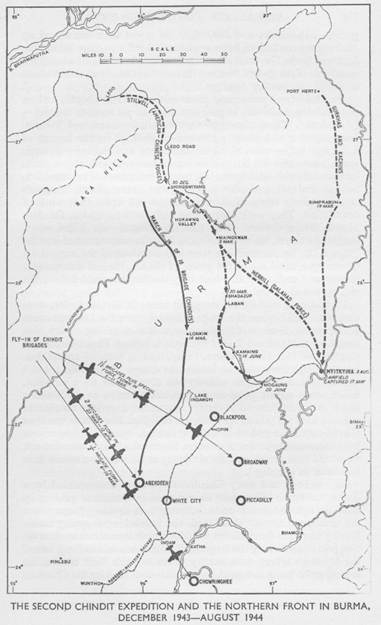

Fig 1:

Merrill’s Marauders area of operations Feb-May 1944 and Ledo Road construction

on the same route.

About the Merrill’s Marauders or

Galahad

At the Quebec Conference in 1943, Allied leaders

decided to form a U.S. long range penetration (LRP) unit that would attack

Japanese troops in Burma. The new U.S. force was directly inspired by, and

partially modeled on British General Orde Wingate's Chindits Long Range

Penetration Force. A call for volunteers attracted around 3,000 men. They came

from Caribbean Defence Command (already jungle trained), South Pacific Command

and Southwest Pacific Command (all already battle tested jungle troops. The unit was officially designated as 5307th Composite Unit

(Provisional) with the code name Galahad.

General Stilwell was worried that 5307th Unit

might also be placed under South East Asia Command (SEAC) under British

influence as it was LRP unit similar to Chindits meant for special operations

in Burma against Japanese. But he was determined to keep exclusive U.S. combat

troops available in the theater out of British command. He was able to persuade

Admiral Lord Mountbatten, the supreme Allied commander of the South East Asia

Command (SEAC), that they should serve under the Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC)

which was controlled by him.

Fig

2: Brigadier General Frank Merrill

Stilwell appointed Brigadier General Frank Merrill (Fig 2

& Fig 3) to command the new LRP unit. Merrill had served earlier as

Military Attaché in Tokyo where he had studied the Japanese language in 1938.

After that he joined General Douglas MacArthur's staff in the Philippines in

1941 as a military intelligence officer. Merrill was on a mission in Rangoon,

Burma, at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack and remained in Burma after the

Japanese invasion. So, he was considered just the right man for the job which

needed combination of Intelligence, Reconnaissance and Combat capabilities in

Jungle terrain of Burma with familiarity of the Japanese.

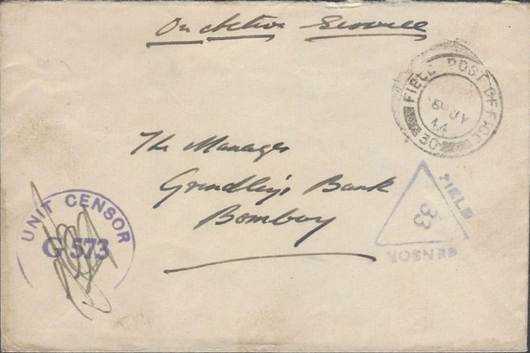

Fig 3: A scarce cover sent by Brig. General Merrill with his

signature at bottom left corner to a Boy Scout troop on Sep 4, 1944, Washington

DC just one month after Merrill’s Marauders were disbanded in August 1944.

Initially,

the plan was to get troops trained under Wingate command along with Chindits

but later the 5307th (Fig 4) trained at Deogarh, India from the end of November

1943 to the end of January 1944. All officers and men received instruction in

scouting and patrolling, stream crossings, weapons, navigation, demolitions,

camouflage, small-unit attacks on entrenchments, evacuation of wounded

personnel, and the then-novel technique of supply by airdrop. Special emphasis

was placed on "jungle lane" marksmanship at pop-up and moving targets

using small arms. In December the 5307th conducted a weeklong maneuver in

coordination with Chindit forces.

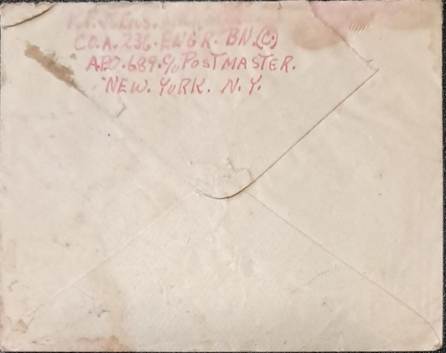

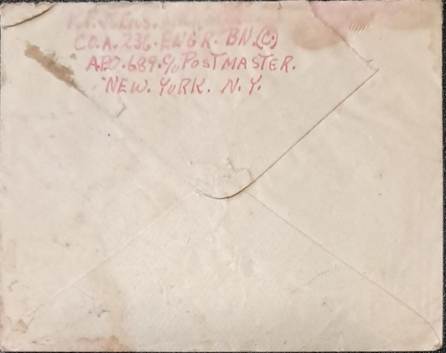

Fig 4: Soldier's

Free Mail from A.P.O. 884 Agra, India by Bronze Star awardee Emil H. Eichhorn

of H.B. Prov. Unit 5307 (Merrill's Marauders) to New York with Passed by US

Army Examiner Censor marking. The cover is dated Dec 14th, 1943,

when they were under training at Deogarh coordinating with Chindits and just

before Merrill’s Marauders started their expedition to Burma in February 1944.

Emil would become part of 2nd Battalion (Blue Combat Team).

Several American war correspondents had come to Deogarh to

hear about the unit and its training; the reporters sat around trying to think

of an appealing nickname for the 5307th that would capture the interest of the

American public. Time correspondent James R. Shepley came up with

"Merrill's Marauders" after viewing the 5307th's

performance on the firing ranges and that name stuck. Afterwards,the 5307th Composite Unit

(Provisional), which was a LRP special operations jungle warfare unit became Merrill’s

Marauders which saw action between Feb-Aug 1944 during the Burma Campaign

of WWII.

Communications

Communications was

most crucial element in this whole campaign. Since the battalions were to be

always on the move and most of the time behind enemy lines, it was necessary to

carry long and short-range radios providing constant communication with headquarter

for orders, supply arrangements, and air cooperation, and within the unit

itself for control of the columns. While they were equipped with long-range

PRC-I (for communication to the base station at Dinjan), SCR 284 radios (for

20-mile range) and later with SCR 300 (Walkie-Talkie), operating and

maintaining them in the terrain was found to be very challenging. This is where

96th Signal Battalion personnel, few assigned with Merrill’s

Marauders battalions to manage communication systems and remaining to support

them from Dinjan and various other locations came handy.

Fig

5: Letter sent from 96th Signal Battalion with APO 487 (Dinjan,

India) with passed by US Army Examiner censor marking on Aug 21, 1944 (just

after battle of Myitkyina was over) to USA.

The 96th Signal

Battalion (Fig 5) was called upon to construct, maintain and operate an intricate

signal communications system in the jungle of Burma. It involved

managing around-the-clock telephone, teletype, radio, and messenger service connecting

and coordinating HQ, Chinese Y-Forces, Merrill’s Marauder’s units and British

Fourteenth Army. The entire battalion saw prolonged service with combat

units serving side by side with Merrill's Marauders along the Ledo Road from

Ledo to Myitkyina, under intense enemy shell fire overcoming various technical

challenges in radio communication.

Campaign

On the advice of

Wingate, the unit was divided into two self-contained combat teams per

battalion. In February 1944, in an offensive designed to disrupt Japanese

offensive operations, three battalions in six combat teams (coded Red, White,

Blue, Khaki, Green, and Orange) marched into Burma. On 24 February, the force

began a 1,000-mile march over the Patkai range and into the Burmese jungle

behind Japanese lines. A total of 2,750 Marauders entered Burma; the remaining

247 men remained in India as headquarters and support personnel. This was

different than Chindits operation where they were airdropped behind enemy lines

in Burma.

Since it was highly

mobile force operating behind the enemy's forward defensive positions, there

was need to find a solution of regular supply to the force. It was not feasible

to maintain regular land supply lines given Ledo Road was still work in

progress and then it would have greatly reduced tactical mobility and would

have made secrecy impossible, contradicting the express purposes of the

operation. Air dropping of food and munitions, though still in an experimental

stage of development, had been satisfactory for Chindit's 1st expedition

of 1943 and was adopted for the LRP missions of the Marauders.

Fig

6: Letter sent from APO 487 Dinjan, India by

2nd Troop Carrier Squadron to APO 81 Camp San Luis Obispo, California dated Nov

21, 1943, with US Army Examiner Censor marking.

At the beginning of

the Marauders' operation the 2nd Troop Carrier Squadron (Fig 6) and later the

1st Troop Carrier Squadron (Fig 7) carried the supplies from the Dinjan base to

forward drop areas. They dropped by parachute engineering equipment,

ammunition, medical supplies, food, clothing and grain flying in all kinds of

weather.

Fig

7: Letter sent from APO 467

Sookerating, Assam, India by 1st Troop Carrier Squadron using concession airmail

to USA dated Dec 13, 1944.

While in Burma, the

Marauders were usually outnumbered by Japanese troops from the 18th Division,

but always inflicted many more casualties than they suffered. Led by Kachin

scouts, and using mobility and surprise, the Marauders harassed supply and

communication lines, shot up patrols, and assaulted Japanese rear areas. The

Japanese were continually surprised by the heavy, accurate volume of fire they

received when attacking Marauder positions. In March they severed Japanese

supply lines in the Hukawng Valley.

In April, the

Marauders were ordered by Stilwell to take up a blocking position at Nhpum Ga

and hold it against Japanese attacks, a conventional defensive action for which

the unit had not been equipped. At times surrounded, the Marauders coordinated

their own battalions in mutual support to break the siege after a series of

fierce assaults by Japanese forces. At Nhpum Ga, the Marauders killed 400

Japanese soldiers, while suffering 57 killed in action, 302 wounded, and 379

incapacitated due to illness and exhaustion. A concurrent outbreak of amoebic

dysentery further reduced their effective strength.

Fig

8 (Rare item): Letter sent by Lt. William Lepore's (1 Bn, White Combat Team) mother from

Everett, MA, US to him in India dated May 8, 1944. Initially addressed to APO

884 (Agra which was serving the 5307th before they were dispatched

to Burma), redirected to APO 883 (Malir, Karachi) where no record was found and

then finally to APO 886 (Karachi) where it was checked in 181st General

Hospital also. There was no record of him found anywhere. Finally, it was found

that he had died in China (June 6, 1944). Perhaps, he got injured during the

campaign and was airlifted to China along with injured Chinese X-forces. He was

awarded Silver Medal.

On May 17, 1944,

after a grueling 100-kilometre march over the 6,600 ft Kumon Mountain range to

Myitkyina, approximately 1,300 remaining Marauders, along with elements of the

42nd and 150th Chinese Infantry Regiments of the X Force, attacked the

unsuspecting Japanese at the Myitkyina airfield. The airfield assault on May 17,

1944 was a complete success; however, the town of Myitkyina could not

immediately be taken with the forces on hand.

Fig

9: Letter sent by Pvt. Julius Michini who was part of 236th Engr.

Battalion on July 27th, 1944, from one the hospitals established

along the Ledo Road after he was wounded in the battle and airlifted. He writes

about losing most of his personal belongings and a good friend in the battle.

Stillwell called upon

the 209th and 236th Engineer Combat Battalion (Fig 9) to

the front lines (who were already working on the Ledo Road behind Marauders).

Men who had been used to driving trucks and operating heavy equipment were

suddenly picking up a rifle and heading into battle. They fought along with

reinforced poorly trained Chinese army and Marauders, bearing the brunt of the

Japanese forces, defending against infantry attacks as well as artillery and

mortar fire. There were 56 killed and 142 wounded persons from the 236th

battalion alone. The battalion (and 209th) received Presidential

Unit Citation for their valiant effort in the battle.

Weakened by hunger,

the 5307th continued fighting through the height of the monsoon season,

worsening the situation; it also transpired that the area around Myitkyina had

the largest reported incidence of scrub typhus, which some Marauders contracted

after sleeping on infected areas of untreated ground, earth or grass. Racked

with bloody dysentery and fevers, sleeping in the mud, Marauders alternately

assaulted, then defended in a seesaw series of brutal conventional infantry

engagements with Japanese forces. The

town finally fell to the Allies on August 3, 1944 due to combined efforts of

various units involved.

In their final

mission against the Japanese base at Myitkyina, the Marauders suffered 272

killed, 955 wounded, and 980 evacuated for illness and disease; some men later died from cerebral malaria, amoebic

dysentery, and/or scrub typhus. By the time the town of

Myitkyina was taken, only about 200 surviving members of the original Marauders

were present. On August 10, 1944, a week after the town's fall to U.S. and

Chinese forces, the 5307th was disbanded with a final total of only 130

combat-effective officers and men (out of the original 2,997).

Fig

10: Letter sent from APO 218

Myitkyina, Burma by 151st Medical Battalion using concession airmail to USA

dated Mar 31, 1945.

Marauders suffered

overall 424 battle related casualties and 1970 disease related casualties. They were evacuated by 71st

Liasion Squadron from the combat zone after they had been treated by medical

corpsmen or surgical teams. Medical battalion detachments marched in the

columns, established aid stations during battle, collected and gave emergency

treatment to casualties, and cared for the sick. Air clearing stations (ACS) were

essential links in the chain of evacuation. The ACS could be opened or closed

on short notice, or it could become the nucleus of a major evacuation center. The

151st Medical Battalion (Fig 10), which became one of the main ground

evacuation units manned the roadside hospitals or in the rear field of the

battle. After initial treatment, most of them were transported to the 20th

General Hospital, the 14th Evacuation Hospital (Fig 11), or the 111th

Station Hospital in the Ledo area.

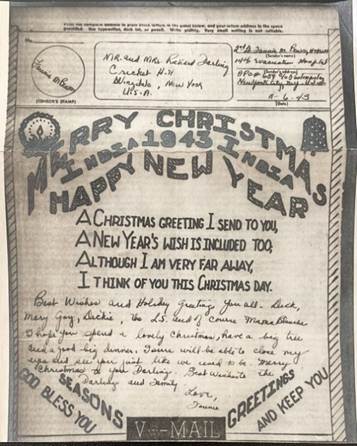

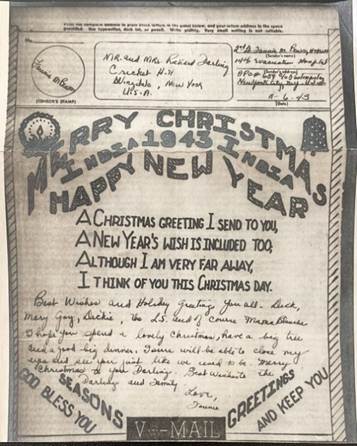

Fig 11: Vmail sent by a female nurse working for 14th

Evacuation Hospital dated June 11, 1943 using APO 689 (Ledo, India). Located at

Ledo Road, Mile 19.

Since the hospitals

were overwhelmed with high number of patients as the battle of Myitkyina

extended, there was need to increase the beds. During June 1944, the 69th General Hospital and the 28th, 32d, 34th, 35th, 50th, and 53d Portable

Surgical Hospitals arrived in Ledo. The 69th general

hospital (Fig 12) was established at Margherita, several miles from the 20th General

Hospital, and the portable surgical hospitals were flown over the “Hump"

to support the Y-Force operating in the Salween River area.

Fig 12: Vmail sent by a sergeant from 69th

General Hospital on Nov 16, 1944 which was located at Margherita (near Ledo).

In slightly more than

five months of combat behind Japanese lines in Burma, the Marauders, who

supported the X Force, advanced roughly thousands of miles through some of the

harshest jungle terrain in the world, fought in five major engagements

(Walawbum, Shaduzup, Inkangahtawng, Nhpum Ga, and Myitkyina)

and engaged in combat with the Japanese Army on thirty-two occasions. Battling

Japanese soldiers, hunger, and disease, they had traversed more jungle on their

long-range patrols than any other U.S. Army unit of the war.

OSS and Kachins

While the main unit of the campaign was

the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), the article won’t be complete if we

don’t mention the contribution of Detachment 101 of the Office of Strategic

Services (OSS) and Kachins. It was the only ground organization involved in all

parts of the campaign. During the long fight, Detachment 101 came of age to

become an indispensable asset for the Allied effort. The unit evolved from an

intelligence collection and sabotage force to an effective guerrilla element.

Fig 13: Letter sent

by Rodney B. Yould, SP1C (P) USNR, APO 629 Chabua, HQ, Detachment 101 to USA;

dated May 13, 1944 during the Marauder’s campaign.

Detachment 101 (Fig 13) was the first overseas unit created under

the Special Operations (SO) branch of the Coordinator of Information (COI), the

predecessor to the OSS. Its agents reported on enemy order of battle, the

political situation in Burma, and the weather. The advantage with Det. 101 was

their agents had infiltrated Burma in 1942 itself. So not only the agents

became familiar with the region, but also, they recruited indigenous agents,

the Kachins.

The

Kachins were fierce warriors, and experts in guerrilla hit-and-run tactics and

jungle craft. They were natural hunters. Best of all, they were pro-Allied and

liked Americans. Every time they got a chance to knock off a [Japanese] patrol

they did it because it was a psychological play. The Kachins sped up the

Marauder advance by providing so much intelligence on Japanese troop movements

that it reduced the need to send out advance reconnaissance patrols. Each of

the three Marauder battalions had two dedicated Kachin guides. They are

credited with saving two-thirds of Merrill’s forces during the siege of Nphum

Ga.They led the Marauders unseen to the

Myitkyina Airfield on May 16, 1944.

Fig 14: Front and last page from the vintage cartoon story called “The Secret Warriors:

OSS in Burma” published by True Comics in 1946 showcasing assistance and

exploits of OSS Detachment 101 and Kachins during Merrill’s Marauders Burma

Campaign.

Detachment 101 was the only American or British ground force that

participated in the Myitkyina Campaign to remain intact afterwards. The

Marauders and the Chindits had been rendered ineffective, mostly by disease.

The remaining Marauders still on their feet became the cadre of the 475th

Infantry Regiment, one of two in the 5332nd Brigade (Provisional), known as the

MARS Task Force. The Chindits never returned to the field and were disbanded in

February 1945. The war was over for them, but not for Detachment 101.

The OSS guerrilla units continued to intercept Japanese elements

fleeing south, preventing them from regrouping, refitting, and being able to

stand against the Allied drive after the monsoon stopped. In August 1944, the

Detachment added several hundred more Japanese killed to their accomplishments.

The reality was that the OSS guerrillas were the only Allied element

maintaining contact with the Japanese south of Myitkyina until October 15, 1944,

when NCAC resumed its offensive. The OSS had proved

itself to be an extremely capable “wild card” maneuver force.

By the time of its deactivation on July 12,

1945, Detachment 101 had scored impressive results. According to official

statistics, with a loss of some 22 Americans, Detachment 101 killed 5,428

Japanese and rescued 574 Allied personnel.

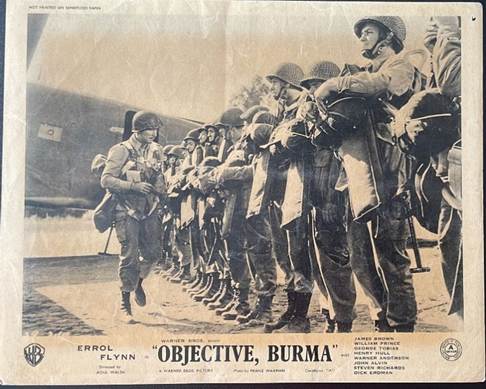

Fig 15: Merrill's Marauders Bronze Medal Collector's edition issued by US Mint

The men of Merrill's Marauders enjoyed the rare

distinction of having each soldier awarded the Bronze Star. Their campaign was

hailed as one of the most successful Guerrilla offensives in most harsh

condition against the Japanese. Warner Bros. decided to make a war film

“Objective, Burma!” starring Errol Flynn (Fig 16), which was loosely based on

the six-month raid by Merrill’s Marauders in the Burma campaign in 1945 itself

immediately after the raid.

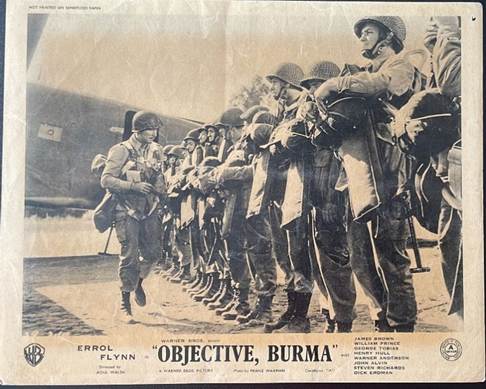

Fig 16: “Objective Burma” an American war movie original

lobby card of 1945 showing actor Errol Flynn inspecting troops.

The

movie also contains a large amount of actual combat footage filmed by U.S. Army

Signal Corps cameramen in the China-Burma-India theatre as well as New Guinea.

It was the studio's sixth most popular film of the year and one of the most

popular movies of 1945 in France.

There

was also the controversy because it was said that movie was inspired by a book

about an attempted British invasion of Burma called Merrill's Marauders and it

was decided to change the troops from being British to American. However,

Merrill's Marauders was an American unit. The movie was withdrawn from release

in the United Kingdom after it infuriated the British public. Prime Minister

Winston Churchill protested the Americanization of the huge and almost entirely

British, Indian and Commonwealth conflict ('1 million men'). It got a second release in the United Kingdom in 1952, when

it was shown with an accompanying apology. The movie was also banned in

Singapore although it was seen in Burma and India.

It

was clear that each allied country had their pride in special operations

conducted by Chindits and Marauders. Together, not only they stopped Japanese

advances to India but also laid ground for Japanese defeat in South East Asia

by reclaiming Burma.

References:

[1]

Merrill’s Marauders February – May

1944, Center of Military History United States Army Washington, D.C., 1990 (https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/marauders/marauders-fw.htm)

[2]

A

Special Forces Model OSS Detachment 101 in the Mytkyina Campaign (https://arsof-history.org/articles/v4n1_myitkyina_part_1_page_1.html#fall)